Bharat Mata

Nationalism In India of Class 10

Bharat Mata

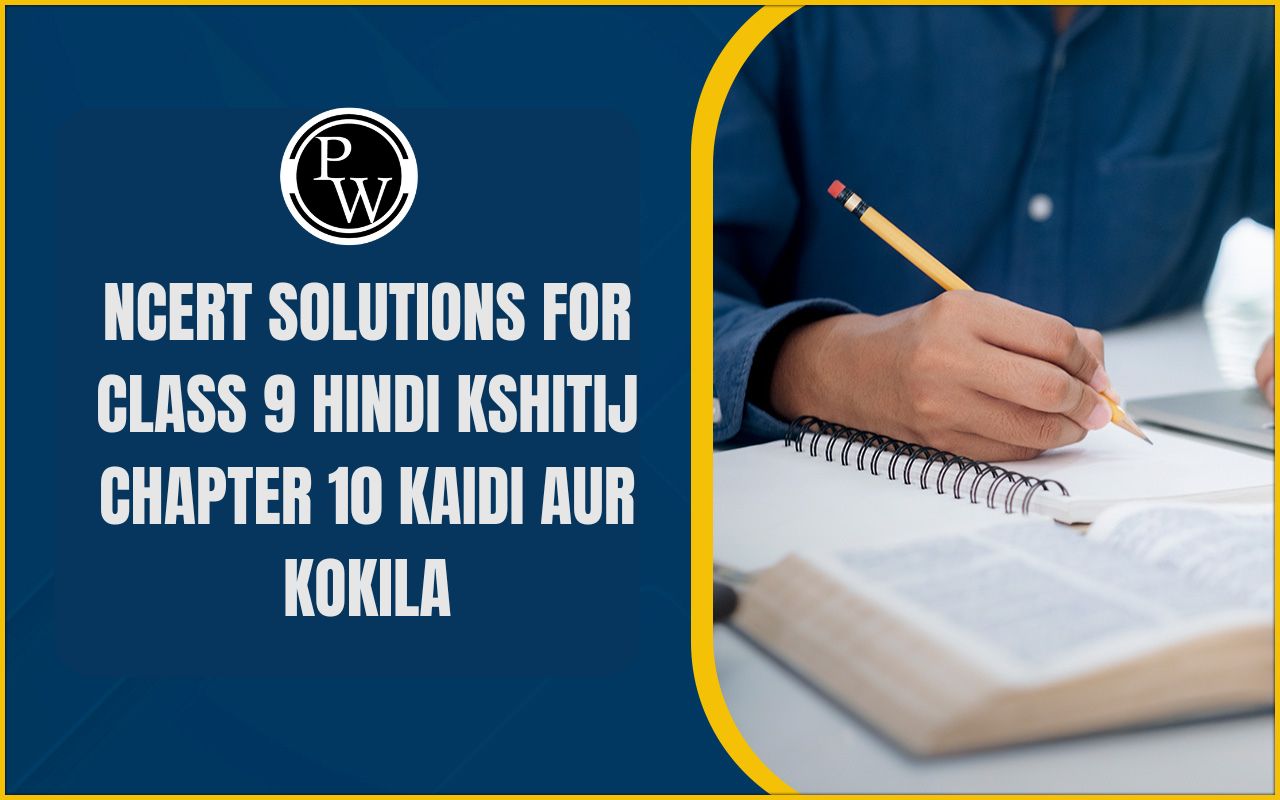

The identity of India came to visually associated with the image of Bharat Mata. The image was first created by Bankim Chandra Chatatopadhyay. In the 1870s he wrote `Vande Materam' as a hymn to the motherland. Later it was included in his novel Anandamath and widely sung during the Swadeshi movement in Bengal. Moved by the Swadeshi movement, Abindranath Tagore painted his famous image of Bharat Mata. In this painting Bharat Mata is portrayed as an ascetic figure: she is calm, composed, divine and spiritual. Devotion to this mother figure came to be seen as evidence of one's nationalism.

Bharat Mata, Rabindranath Tagore, 1905

Jawaharlal Nehru

NATIONAL SONG:

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhya in the 1870 wrote Vande Mataram as a hymn to the motherland. Later it was included in his novel “Anandmath.”

FOLKLORES:

Ideas of nationalism also developed through a movement to revive Indian folklore. In late-nineteenth-century India, nationalists began recording folk tales sung by bards and they toured villages to gather folk songs and legends. These tales, they believed, gave a true picture of traditional culture that had been corrupted and damaged by outside forces. It was essential to preserve this folk tradition in order to discover one’s national identity and restore a sense of pride in one’s past. In Bengal, Rabindranath Tagore himself began collecting ballads, nursery rhymes and myths, and led the movement for folk revival. In Madras, Natesa Sastri published a massive four-volume collection of Tamil folk tales, The Folklore of Southern India. He believed that folklore was national literature; it was ‘the most trustworthy manifestation of people’s real thoughts and characteristics’.

NATIONAL FLAG

As the national movement developed, nationalist leaders became more and more aware of such icons and symbols in unifying people and inspiring in them a feeling of nationalism. During the Swadeshi movement in Bengal, a tricolour flag (red, green and yellow) was designed. It had eight lotuses representing eight provinces of British India, and a crescent moon, representing Hindus and Muslims. By 1921, Gandhiji had designed the Swaraj flag. It was again a tricolour (red, green and white) and had a spinning wheel in the centre, representing the Gandhian ideal of self-help. Carrying the flag, holding it aloft, during marches became a symbol of defiance.

REINTERPRETATION OF HISTORY

- Looking into the Glorious past by the end of the 9th century many Indians felt that to instill a sense of pride in the nation, Indian history had to be thought about differently. Indians started looking into the past to rediscover India’s achievements.

- They wrote about the development in ancient times when art, architecture, science, mathematics, religion, culture, law, crafts and trade had flourished.

- When past being glorified was Hindu and celebrated images were drawn from Hindu iconology, the people of other communities felt left-out.

ROLE OF GANDHl JI IN INDIA'S STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE:

Perhaps there is no other Indian who made so great a contribution as Mahatma Gandhi to the achievement of independence for India. He dominated the scene of the Indian politics from 1919 to 1947 A.D. So most of the Indian historians have given the name of "The Gandhi Era" to this period. There is no exaggeration in it. He united all the elements of the Indian National Movement under his banner. Actively participating himself in the struggle for freedom, he guided other leaders as well.

He made the powerful and strong. British Government yield by the use of his peaceful weapon of non−violence. He did not make use of any violent means to achieve freedom or independence but employed the peaceful movement of Non Cooperation Sataygrha and Boycott Swadeshi, etc. for this purpose.

He laboured hard to keep Hindus and Muslims united so that the British policy of 'Divide and Rule' should not succeed.

He did a lot for the uplift of the Harijans and laboured hard to get them a respectable position in the society.

In fact Gandhiji was always ready to sacrifice his all for the sake of his countrymen and his motherland. For this he had to pass through many risks. He had to bear the lathi blow and had also to go to the jail many a time. Even then he did not give up his struggle and continued his efforts as a brave soldier. His able leadership and sacrifices ultimately compelled the British to leave India on 15th August, 1947 A.D. It was he who had made the Congress movement a mass movement. Take any of the movements the Non-cooperation Movement, the Satyagraha Movement, the Civil Disobedience Movement, the Quit India Movement, it were the common masses that played the major role and took an active part in the freedom movement of the country. It was he who inspired the people with new confidence in their fight for freedom. The common masses realized the strength of their unity and cooperation and learnt the lessons in self sacrifice and self reliance.

In February 1922, Mahatma Gandhi decided to withdraw the Non-Cooperation Movement. He felt the movement was turning violent in many places and satyagrahis needed to be properly trained before they would be ready for mass struggles. Within the Congress, some leaders were by now tired of mass struggles and wanted to participate in elections to the provincial councils that had been set up by the Government of India Act of 1919. They felt that it was important to oppose British policies within the councils, argue for reform and also demonstrate that these councils were not truly democratic. C. R. Das and Motilal Nehru formed the Swaraj Party within the Congress to argue for a return to council politics. But younger leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose pressed for more radical mass agitation and for full independence. In such a situation of internal debate and dissension two factors again shaped Indian politics towards the late 1920s. The first was the effect of the worldwide economic depression. Agricultural prices began to fall from 1926 and collapsed after 1930. As the demand for agricultural goods fell and exports declined, peasants found it difficult to sell their harvests and pay their revenue. By 1930, the countryside was in turmoil.

.png----FileNotFound----)

SIMON COMMISSION:

Against this background the new Tory government in Britain constituted a Statutory Commission under Sir John Simon. Set up in response to the nationalist movement, the commission was to look into the functioning of the constitutional system in India and suggest changes. The problem was that the commission did not have a single Indian member. They were all British.

When the Simon Commission arrived in India in 1928, it was greeted with the slogan ‘Go back Simon’. All parties, including the Congress and the Muslim League, participated in the demonstrations. In an effort to win them over, the viceroy, Lord Irwin, announced in October 1929, a vague offer of ‘dominion status’ for India in an unspecified future, and a Round Table Conference to discuss a future constitution.

.png----FileNotFound----)

This did not satisfy the Congress leaders. The radicals within the Congress, led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, became more assertive. The liberals and moderates, who were proposing a constitutional system within the framework of British dominion, gradually lost their influence. In December 1929, under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, the Lahore Congress formalised the demand of ‘Purna Swaraj’ or full independence for India. It was declared that 26 January 1930, would be celebrated as the Independence Day when people were to take a pledge to struggle for complete independence. But the celebrations attracted very little attention. So Mahatma Gandhi had to find a way to relate this abstract idea of freedom to more concrete issues of everyday life.

SALT MARCH:

Mahatma Gandhi found in salt a powerful symbol that could unite the nation. On 31 January 1930, he sent a letter to Viceroy Irwin stating eleven demands. Some of these were of general interest; others were specific demands of different classes, from industrialists to peasants. The idea was to make the demands wide-ranging, so that all classes within Indian society could identify with them and everyone could be brought together in a united campaign. The most stirring of all was the demand to abolish the salt tax. Salt was something consumed by the rich and the poor alike, and it was one of the most essential items of food. The tax on salt and the government monopoly over its production, Mahatma Gandhi declared, revealed the most oppressive face of British rule.

Mahatma Gandhi’s letter was, in a way, an ultimatum. If the demands were not fulfilled by 11 March, the letter stated, the Congress would launch a civil disobedience campaign. Irwin was unwilling to negotiate. So Mahatma Gandhi started his famous salt march accompanied by 78 of his trusted volunteers. The march was over 240 miles, from Gandhiji’s ashram in Sabarmati to the Gujarati coastal town of Dandi. The volunteers walked for 24 days, about 10 miles a day. Thousands came to hear Mahatma Gandhi wherever he stopped, and he told them what he meant by swaraj and urged them to peacefully defy the British. On 6 April he reached Dandi, and ceremonially violated the law, manufacturing salt by boiling sea water.

This marked the beginning of the Civil Disobedience Movement. This was altogether different from the Non-cooperation Movement. People were now asked not only to refuse cooperation with the British, as they had done in 1921-22, but also to break colonial laws. Thousands in different parts of the country broke the salt law, manufactured salt and demonstrated in front of government salt factories. As the movement spread, foreign cloth was boycotted, and liquor shops were picketed. Peasants refused to pay revenue and chaukidari taxes, village officials resigned, and in many places forest people violated forest laws – going into Reserved Forests to collect wood and graze cattle.

.png----FileNotFound----)

RESPONSE OF BRITISH RULERS:

Worried by the developments, the colonial government began arresting the Congress leaders one by one. This led to violent clashes in many palaces. When Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a devout disciple of Mahatma Gandhi, was arrested in April 1930, angry crowds demonstrated in the streets of Peshawar, facing armoured cars and police firing. Many were killed. A month later, when Mahatma Gandhi himself was arrested, industrial workers in Sholapur attacked police posts, municipal buildings, law courts and railway stations – all structures that symbolised British rule. A frightened government responded with a policy of brutal repression. Peaceful satyagrahis were attacked, women and children were beaten, and about 100,000 people were arrested.

HOW DID THE DIFFERENT SOCIAL GROUPS PARTICIPATE IN THE CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE MOVEMENT:

- Rich peasant communities: The patidars of Gujrat and the Jats of U.P. were active in the movement. They were the producers of commercial crops and were hard hit by the trade depression.

- The refusal of the government to reduce the revenue demand led to wide spread resentment. They supported the civil disobedience movement because for them the fight for Swaraj was struggle against high revenues.

- Poor peasants: They were small tenants cultivating land they had rented from the landlords. As the depression continued cash incomes became lesser, they found it difficult to pay the rent.

- Business class: During the First World War Indian merchants had made huge profits and had become powerful. They now reacted against colonial policies which restricted their business activities.

- They formed the Indian Industrial and commercial congress and the federation of the Indian chamber of commerce and industries (FICCI). Led by Purushottamdas Thakur & G.D. Birla they joined civil Disobedience movement.

They saw Swaraj as a time when there would be no restriction on trade and industry.

- Industrial working lass: They fought against low wages, poor working condition. There were strikes, protest rallies and boycott campaigns. Although they kept their distance away from the INC as INC was close to Businessmen.

- Women: For Gandhiji salt march thousands of women came out of their homes to listen to him. In urban area they were from high caste families and in rural areas they came from rich peasant households. They began to see the service to the nation as a sacred duty of women.

THE LIMITS OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE:

Not all social groups were moved by the abstract concept of swaraj.

(i) One such group was the "Untouchables" who now called themselves "Dalits" or the oppressed, Mahatma Gandhi called the untouchables, harijans and declared that India would not achieve ‘Swaraj' for hundred years, if untouchability was not totally eliminated. He organized Satyagraha to secure them entry into temples, and access to public wells, tanks, roads and schools.

The Dalits - Wanted a political solution for their problems. They demanded reservation of seats, in educational institutes, separate electorate to choose their own candidates to the legislative councils. They wanted to solve their social problems.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the leader of the Dalits, formed an association in 1930, called the Depressed Classes Association. He clashed with Gandhiji at the Second Round Table Conference by demanding separate electorates for dalits. The British Government accepted Dr. Ambedkar's demand. Gandhiji began a fast unto death. He believed that the Dalits would never be integrated into society, if they got separate electorates Dr. Ambedkar finally signed a pact with Gandhiji in September 1932, called the Poona Pact. It gave reserved seats in provincial and Central Legislative Councils to the Depressed Classes. They were to be voted in by the general electorate.

(ii) Muslim political organisations also kept away from Civil Disobedience Movement.

(A) Muslims felt alienated from Congress after the decline of Non-Cooperation - Khilafat Movement.

(B) From mid-1920's the Congress seemed to be more visibly associated with Hindu religions nationalist groups like the Hindu Mahasabha.

(C) There were Hindu-Muslim Clashes and riots in many cities, which further worsened the relations between the two communities.

Attempt was made in 1927 by the Congress and Muslim League to form an alliance. It seemed possible as M.A. Jinnah, one of the leaders of Muslim League, agreed to give up the demand for separate electorates if:

(A) Muslims were assured reserved seats in Central Assembly.

(B) Representation in proportion to population in the Muslim dominated provinces, (Bengal and Punjab). Negotiations failed in 1928 when M.R. Jayakar of the Hindu Mahasabha strongly opposed efforts at compromise.

So the Civil Disobedience Movement started in an atmosphere of distrust and suspicion between the two communities. Muslims feared that their culture and identity would be submerged under the Hindu majority dominance.

THE SENSE OF COLLECTIVE BELONGING:

- A sense of collective belonging came partly through the experience of united struggles.

- These were also a variety of cultural processes through which nationalism captured people’s imagination.

- Like history, fiction folklore and son popular prints and symbols all played a part in the making of nationalism.

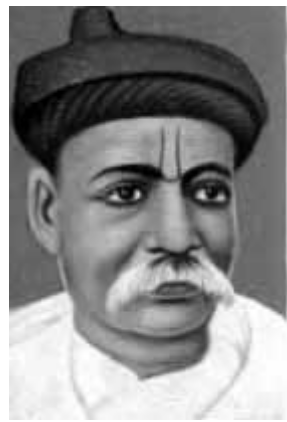

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, an early-nineteenth century print

- Within the congress, some leaders were by now tired of mass struggle and wanted to participate in the elections to the provincial councils that had been set up by the government of India act of 1919.

- They felt it was important to oppose the British policies within the councils.

- C.R. Das and Motilal Nehru formed the Swaraj Party within the Congress to argue for a return to council politics.

- Young leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose wanted more radical mass struggle for independence.

TWO FACTORS THAT SHAPED THE INDIAN POLITICS:

- The first factor was the effect of the world wide economic depression. Agricultural prices began to fall from 1927 and collapsed after 1930.

- Demand for agricultural goods fell and exports declined. The peasants found it difficult to sell their harvests and pay revenue.

- The second factor the new Tory government in Britain sent the Simon commission. It was to look into the functioning of the constitutional system in India and suggest changes.

- All parties, including the Congress and the Muslim League, participated in the demonstrations.

- In an effort to win them over, the viceroy, Lord Irwin, announced in October 1929, a vague offer of ‘dominion status’ for India in an unspecified future, and a Round Table Conference to discuss a future constitution.

- This did not satisfy the Congress leaders. The radicals within the Congress, led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, became more assertive.

- The liberals and moderates, who were proposing a constitutional system within the framework of British dominion, gradually lost their influence.