The Strange Case Of Britain

Rise Of Nationalism In Europe of Class 10

The Strange Case Of Britain

In Britain the formation of the nation-state was not the result of a sudden upheaval or revolution. It was the result of a long-drawn-out process. There was no British nation prior to the eighteenth century. The primary identities of the people who inhabited the British Isles were ethnic ones – such as English, Welsh, Scot or Irish. All of these ethnic groups had their own cultural and political traditions. But as the English nation steadily grew in wealth, importance and power, it was able to extend its influence over the other nations of the islands. The English parliament, which had seized power from the monarchy in 1688, was the instrument through which a nation-state, with England at its centre, came to be forged.

The Act of Union (1707) between England and Scotland that resulted in the formation of the ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain’ meant, in effect, that England was able to impose its influence on Scotland. The British parliament was henceforth dominated by its English members. The growth of a British identity meant that Scotland’s distinctive culture and political institutions were systematically suppressed. The Catholic clans that inhabited the Scottish Highlands suffered terrible repression whenever they attempted to assert their independence. The Scottish Highlanders were forbidden to speak their Gaelic language or wear their national dress, and large numbers were forcibly driven out of their homeland.

Ireland suffered a similar fate. It was a country deeply divided between Catholics and Protestants. The English helped the Protestants of Ireland to establish their dominance over a largely Catholic country. Catholic revolts against British dominance were suppressed. After a failed revolt led by Wolfe Tone and his United Irishmen (1798), Ireland was forcibly incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1801.

A new ‘British nation’ was forged through the propagation of a dominant English culture. The symbols of the new Britain – the British flag (Union Jack), the national anthem (God Save Our Noble King), the English language – were actively promoted and the older nations survived only as subordinate partners in this union.

VISUALISING THE NATION:

- Artists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries found a way out by personifying a nation.

- In other words, they represented a country as if it were a person. Nations were then portrayed as female figures.

- The female form that was chosen to personify the nation did not stand for any particular woman in real life; rather it sought to give stand for any particular woman in real life; rather it sought to give the abstract idea of the nation a concrete form.

- That is, the female figure became an allegory of the nation.

- The ideas of liberty, justice and the republic during the French revolution were represented by the artists as female allegory.

- These ideals were represented through specific objects or symbols.

- The nations were represented by a female allegories invented by artists during the 19th century.

MARIANNE ITS SIGNIFICANCE

- Marianne is a popular Christian name. This name was given to the imaginary figure that was chosen to represent France as a nation. In other words, Marianne, as a female figure, was an allegory for France, a nation.

- Characteristics of Marianne were symbolic of Liberty and the Republic. These were represented by such symbols as the red cap, the tricolour and the cockage. Statues of Marianne were erected in public squares to remind the public of the national symbol of unity.

GERMANIA:

- Germania was an imaginary female figure. It was chosen as an allegory for the German nation.

- Germania wears a crown of oak leaves, as the German oak stands for heroism.

Meanings of the symbols:

|

Attribute |

Significance |

|

Broken chains |

Being freed |

|

Breastplate with eagle |

Symbol of the German empire-strength |

|

Crown of oak leaves |

Heroism |

|

Sword |

Readiness to fight |

|

Olive branch around the sword |

Willingness to make peace |

|

Black, red and gold tricolour |

Flag of the liberal-nationalists in 1848, banned by the Dukes of the German states |

|

Rays of the rising sun |

Beginning of a new era |

Activity

- Germania wears a crown of oak leaves, as the German oak stands for heroism.

|

With the help of the chart in Box 3, identify the attributes of Veit’s Germania and interpret the symbolic, meaning of the painting. In an earlier allegorical rendering of 1836, Veit had portrayed the Kaiser’s crown at the place where he has now located the broken chain. Explain the significance |

|

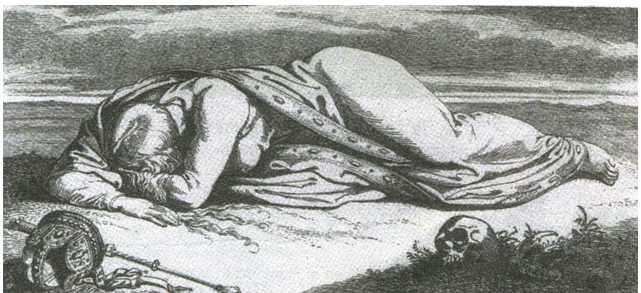

The fallen Germania, Julius Hubner, 1850

HISTORICAL EVENTS HUBNER REFERRING TO IN THIS ALLEGORICAL VISION OF THE NATION:

- Hubner has painted a disgraced Germania. Germania was an allegory for German pride and heroism.

- One can see the German pride and strength razed down to the ground. The crown is biting the dust. Breastplate is missing, as is the tricolour. Death is stalking the land.

- It is sunset for Germany with dark clouds hovering all-around.

- The painting depicts a deep sense of hurt and anguish that the Germans experience at the failure of the Frankfurt Parliament in 1848.

- In the German regions, educated middle classes came together in the city of Frankfurt. They voted for an all-German National Assembly.

- Frankfurt Parliament was convened on May 18, 1848 in the Church of St. Paul. The elected representatives drafted a constitution for a German nation to be headed by a monarchy subject to a parliament.

- Friedrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia, rejected this draft. He joined other monarchs to oppose the elected assembly. In the end, troops were called in and the assembly was forced to disband.

Germania, Philip Veit, 1848

The artist prepared this painting of Germania on a cotton banner, as it as meant to hang from the ceiling of the Church of St. Paul where the Frankfurt parliament was convened in March, 1848.

NATIONALISM AND IMPERIALISM:

(i) By the last quarter of the nineteenth century the major European powers manipulated the nationalist aspirations of the subject peoples in Europe to further their own imperialist aims.

(ii) The most serious source of nationalist tension in Europe after 1871 was the area called the Balkans. The Balkans was a region of geographical and ethnic variation comprising modern-day Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Greece, Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Solvenia, Serbia and Montenegro whose inhabitants were broadly known as the Slavs. A large part of the Balkans was under the control of the Ottoman empire.

(iii) The spread of the ideas of romantic nationalism in the Balkans together with the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire made this region very explosive. One by one, its European subject nationalities broke away from its control and declared independence.

(iv) All through the nineteenth century the Ottoman Empire had sought to strengthen itself through modernisation and internal reforms but with very little success. One by one, its European subject nationalities broke away form its control and declared independence.

(v) The Balkan area became an area of intense conflict. The Balkan states were fiercely jealous of each other and each hoped to gain more territory at the expense of the others.

(vi) During this period, there was intense rivalry among the European powers over trade and colonies as well as naval and military might. Each power- Russia, Germany, England, Austro-Hungary-was keen on countering the hold of other powers over the Balkans, and extending its own control over the area. This led a series of wars in region and finally the First World War. Nationalism, aligned with imperialism, led Europe to disaster in 1914.

(vii)Many countries in the world which had been colonised by the European power in the nineteenth century began to oppose imperial domination. The anti-imperial movements that developed everywhere were nationalist, in the sense that they all struggled to form independent nation-states, and were inspired by a sense of collective national unity, forged in confrontation with imperialism.

The idea that societies should be organised into 'nation-states' came to be accepted as natural and universal.