Print Comes To Europe

Print Culture And The Modern World of Class 10

For centuries, silk and spices from China flowed into Europe through the silk route. In the eleventh century, Chinese paper reached Europe via the same route. Paper made possible the production of manuscripts, carefully written by scribes. Then, in 1295, Marco Polo, a great explorer, returned to Italy after many years of exploration in China. Marco Polo brought the knowledge of printing technology back with him. Now Italians began producing books with woodblocks, and soon the technology spread to other parts of Europe. Luxury editions were still handwritten on very expensive vellum, meant for aristocratic circles and rich monastic libraries which scoffed at printed books as cheap vulgarities. Merchants and students in the university towns bought the cheaper printed copies.

As the demand for books increased, booksellers all over Europe began exporting books to many different countries. Book fairs were held at different places. Production of handwritten manuscripts was also organised in new ways to meet the expanded demand. Scribes or skilled handwriters were no longer solely employed by wealthy or influential patrons but increasingly by booksellers as well. More than 50 scribes often worked for one bookseller.

LIMITATIONS OF HANDWRITTEN MANUSCRIPTS:

It could not satisfy the ever-increasing demand for books. Copying was an expensive, laborious and time-consuming business. Manuscripts were fragile, awkward to handle, and could not be carried around or read easily. Their circulation therefore remained limited.

Hence woodblock printing gradually became more and more popular.

GUTENBERG AND THE PRINTING PRESS:

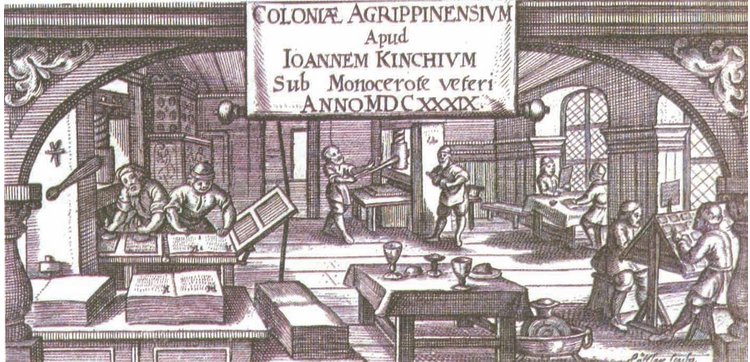

- Gutenberg was the son of a merchant and grew up on a large agricultural estate.

- He learnt the art of polishing stones, became a master goldsmith, and also acquired the expertise to create lead moulds used for making trinkets.

- Gutenberg adapted existing technology to design his innovation.

- By 1448, Gutenberg perfected the system. The first book he printed was the Bible. About 180 copies were printed and it took three years to produce them. By the standards of the time this was fast production.

- Printed books at first closely resembled the written manuscripts in appearance and layout.

- In fact, printed books at first closely resembled the written manuscripts in appearance and layout.

- Borders were illuminated by land with foliage and other patterns, and illustrations were painted.

- In the books printed for the rich, space for decoration was kept blank on the printed page.

- In the hundred years between 1450 and 1550, printing presses were set up in most countries of Europe. Printers from Germany traveled to other countries, seeking work and helping start new presses.

- The shift from hand printing to mechanical printing led to the print revolution.

- The second half of the fifteenth century saw 20 million copies of printed books flooding the markets in Europe. The number went up in the sixteenth century to about 200 million copies.

A printer’s workshop, sixteenth century