Print Culture And The French Revolution

Print Culture And The Modern World of Class 10

Print Culture And The French Revolution

Print popularised the ideas of the Enlightenment thinkers. Collectively, their writings provided a critical commentary on tradition, superstition and despotism. They argued for the rule of reason rather than custom, and demanded that everything be judged through the application of reason and rationality. They attacked the sacred authority of the Church and the despotic power of the state, thus eroding the legitimacy of a social order based on tradition. The writings of Voltaire and Rousseau were read widely; and those who read these books saw the world through new eyes, eyes that were questioning, critical and rational.

Print created a new culture of dialogue and debate. All values, norms and institutions were re-evaluated and discussed by a public that had become aware of the power of reason, and recognised the need to question existing ideas and beliefs. Within this public culture, new ideas of social revolution came into being.

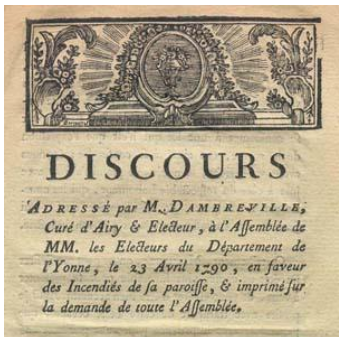

By the 1780s there was an outpouring of literature that mocked the royalty and criticised their morality. In the process, it raised questions about the existing social order. Cartoons and caricatures typically suggested that the monarchy remained absorbed only in sensual pleasures while the common people suffered immense hardships. This literature circulated underground and led to the growth of hostile sentiments against the monarchy.

French Revolution Pamphlets

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY:

The nineteenth century saw vast leaps in mass literacy in Europe, bringing in large numbers of new readers among children, women and workers.

(a) Children, Women and Workers:

(i) From the late nineteenth century, children became an important category of readers. Production of school textbooks became critical for the publishing industry. A children's press, devoted to literature for children alone, was set up in France in 1857. This press published new works as well as old fairy tales and folktales. Anything that was considered unsuitable for children or would appear vulgar to the elites, was not included in the published version.

(ii) Women became important as readers as well as writers. Penny magazines were especially meant for women, as were manuals teaching proper behaviour and housekeeping. Some of the best-known novelists were women: Jane Austen, the Bronte sisters, George Eliot. Their writings became important in defining a new type of woman: a person with will, strength of personality, determination and the power to think.

(iii) In the nineteenth century, lending libraries in England became instruments for educating white-collar workers, artisans and lower-middle-class people. After the working day was gradually shortened from the mid-nineteenth century, workers had some time for self-improvement and self - expression. They wrote political tracts and autobiographies in large numbers.

FURTHER INNOVATIONS:

- By the late eighteenth century, the press came to be made out of metal. Through the nineteenth century, there were a series of further innovations in printing technology.

- By the mid-nineteenth century, Richard M. Hoe of New York had perfected the power-driven cylindrical press.

- This was capable of printing 8,000 sheets per hour. This press was particularly useful for printing newspapers.

- In the late nineteenth century, the offset press was developed which could print up to six colours at a time.

- From the turn of the twentieth century, electrically operated presses accelerated printing operations.

- Methods of feeding paper improved, the quality of plates became better, automatic paper reels and photoelectric controls of the colour register were introduced.

- The accumulation of several individual mechanical improvements transformed the appearance of printed texts.

- Serialized writing was the new product introduced by the printers and publishers as new strategies to sell their products.

- Nineteenth-century periodicals serialized important novels, which gave birth to a particular way of writing novels.

- In the 1920s in England, popular works were sold in cheap series, called the Highlight Series.

- With the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s, publishers feared a decline in book purchases. To sustain buying they brought out cheap paperback editions.

INDIA AND THE WORLD OF PRINT:

(a) Manuscripts Before the age of print:

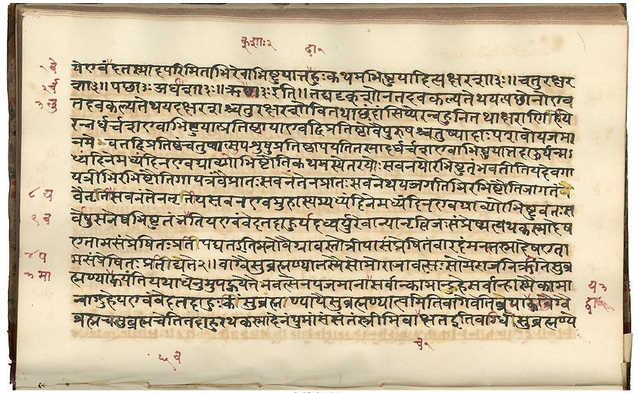

India had a very rich and old tradition of hand written manuscripts in Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, as well as in various vernacular languages. Manuscripts continued to be produced till well after the introduction of print, down to the late nineteenth century.

Manuscripts were however very expensive and fragile and had to be handled carefully, and they could not be read easily as the script were written in different styles. So the manuscripts were not widely used in everyday life.

Page from the Rig-Veda.

PRINT COMES TO INDIA:

The printing press first came to Goa with Portuguese missionaries in the mid-sixteenth century. Jesuit priests learnt Konkani and printed several tracts. By 1674, about 50 books had been printed in the Konkani and in Kanara languages. Catholic priests printed the first Tamil book in 1579 at Cochin, and in 1713 the first Malayalam book was printed by them. By 1710, Dutch Protestant missionaries had printed 32 Tamil texts, many of them translations of older works.

The English language press did not grow in India till quite late even though the English East India Company began to import presses from the late seventeenth century.

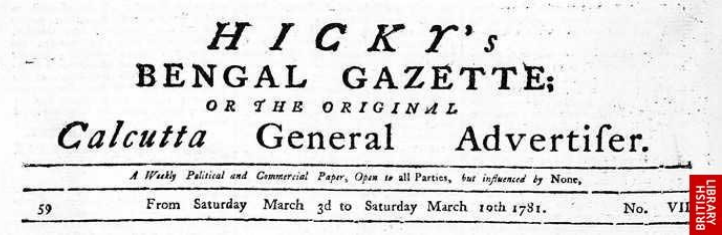

From 1780, James Augustus Hickey began to edit the Bengal Gazette, a weekly magazine that described itself as ‘a commercial paper open to all, but influenced by none’. So it was private English enterprise; proud of its independence from colonial influence; that began English printing in India. Hickey published a lot of advertisements, including those that related to the import and sale of slaves. But he also published a lot of gossip about the Company’s senior officials in India. Enraged by this, Governor-General Warren Hastings persecuted Hickey, and encouraged the publication of officially sanctioned newspapers that could counter the flow of information that damaged the image of the colonial government.

Bengal Gazette

By the close of the eighteenth century, a number of newspapers and journals appeared in print. There were Indians, too, who began to publish Indian newspapers. The first to appear was the weekly Bengal Gazette, brought out by Gangadhar Bhattacharya, who was close to Rammohun Roy.

RELIGIOUS REFORM AND PUBLIC DEBATES:

- Different groups confronted the changes happening within colonial society in different ways, and offered a variety of new interpretation of the beliefs of different religions.

- Some criticized existing practices and campaigned for reform, while others countered the arguments of reforms.

- These debates were carried out in public and in print. Printed tracks and newspapers not only spread the new ideas, but they shaped the nature of the debate.

PRINTS AND SOCIAL REFORM:

In north India, the ulama were deeply anxious about the collapse of Muslim dynasties. They feared that colonial rulers would encourage conversion, change the Muslim personal laws. To counter this, they used cheap lithographic presses, published Persian and Urdu translations of holy scriptures, and printed religious newspapers and tracts. The Deoband Seminary, founded in 1867, published thousands upon thousands of fatwas telling Muslim readers how to conduct themselves in their everyday lives, and explaining the meanings of Islamic doctrines. All through the nineteenth century, a number of Muslim sects and seminaries appeared, each with a different interpretation of faith, each keen on enlarging its following and countering the influence of its opponents. Urdu print helped them conduct these battles in public.

PRINT AND THE HINDUS:

(i) The first printed edition of the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas came out from Calcutta in 1810.

(ii) The mid-nineteenth century, cheap lithographic editions flooded the north Indian markets.

(iii) From the 1880s, the Naval Kishore Press at Lucknow and the Shri Venkateshwar Press in Bombay published many religious texts in vernaculars.

Religious texts and books started reaching a very wide circle of people, encouraging debates and controversies within and among different religions. Print did not only stimulate the publication of conflicting opinions amongst communities, but it also connected communities and people in different parts of India, creating pan-Indian identities.