Industrialization In The Colonies

The Age Of Industrialization of Class 10

Industrialization In The Colonies

THE AGE OF INDIAN TEXTILES:

- Before the age of machine industries, silk and cotton goods from India dominated the international market in textiles.

- Fine variety of clothes was in great demand in the west.

- Armenian and Persian merchants took the goods from Punjab to Afghanistan, eastern Persia and Central Asia. Bales of fine textiles were carried on camelback via the north-west frontier, through mountain passes and across deserts.

- Surat on the Gujarat coast connected India to the Gulf and Red Sea Ports; Masulipatam on the Coromandel Coast and Hooghly in Bengal had trade links with Southeast Asian ports.

- A variety of Indian merchants and bankers were involved in this network of export trade – financing production, carrying goods and supplying exporters.

- The supply merchants linked the port towns to the inland region. They gave advances to the weavers, purchased the woven cloth from weaving villages, and brought the supply to the port.

- At the port, the big shippers and export merchants had brokers who negotiated the price and bought goods from the supply merchants operating inland.

RISE OF EUROPEAN COMPANIES:

The European companies gradually gained power – first securing a variety of concessions from local courts, then the monopoly rights to trade. This resulted in a decline of the old ports of Surat and Hooghly through which local merchants had operated. Exports from these ports fell dramatically, the credit that had financed the earlier trade began drying up, and the local bankers slowly went bankrupt.

In the last years of the seventeenth century, the gross value of trade that passed through Surat had been Rs 16 million. By the 1740s it had slumped to Rs 3 million. While Surat and Hooghly decayed, Bombay and Calcutta grew. This shift from the old ports to the new ones was an indicator of the growth of colonial power. Trade through the new ports came to be controlled by European companies, and was carried in European ships. While many of the old trading houses collapsed, those that wanted to survive had to now operate within a network shaped by European trading companies.

WHAT HAPPENED TO WEAVERS ?

Before establishing political power in Bengal and Carnatic in the 1760s and 1770s, the East India Company had found it difficult to ensure a regular supply of goods for export. Once the East India Company established political power, it could assert a monopoly right to trade. It proceeded to develop a system of management and control that would eliminate competition, control costs, and ensure regular supplies of cotton and sism goods. This it did through a series of steps.

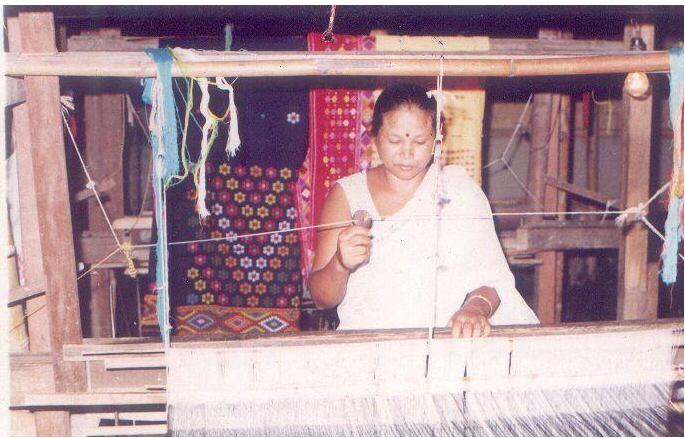

A weaver at work

(i) The Company tried to eliminate the existing traders and brokers by appointing paid servants called the gumasta to supervise weavers, collect supplies, and examine the quality of cloth.

(ii) It prevented Company weavers from dealing with other buyers by the system of advances. Once an order was placed, the weavers were given loans to purchase the raw material for their production. Those who took loans had to hand over the cloth they produced to the gomastha.

EFFECTS:

(i) Many weavers had small plots of land which they had earlier cultivated along with weaving, but now they had to lease out the land and devote all their time to weaving.

(ii) In many weaving villages there were reports of clashes between weavers and gomasthas. The gomasthas acted arrogantly, marched into villages with sepoys and peons, and punished weavers for delays in supply - often beating and flogging them. The weavers lost the space to bargain for prices and sell to different buyers, and the loans they had accepted tied them to the Company.

(iii) In many places in Carnatic and Bengal, weavers deserted villages and migrated, setting up looms in other villages where they had some family relation. Elsewhere, weavers along with the village traders revolted, began refusing loans, closing down their workshops and taking to agricultural labour.

CLASHES BETWEEN WEAVER AND GOMASTHAS

- Earlier supply merchants had very often lived within the weaving village, and had a close relationship with the weavers, looking after their needs and helping them in times of crisis.

- The new gomasthas were outsiders, with no long-term social link with the village.

- They acted arrogantly, marched into villages with sepoys and peons, and punished weavers for delays in supply-often beating and flogging them.

Weaving site

- The weavers lost the space to bargain for prices and sell to different buyers : the price they received from the Company was miserably low and the loans they had accepted tied them to the Company.

- In many places in Carnatic and Bengal, weavers deserted villages and migrated, setting up looms in other villages where they had some family relation.

- At other places weavers and the local traders revolted against gomasthas and company officials.