The Coming Up Of The Factory

The Age Of Industrialization of Class 10

The Coming Up Of The Factory

- The earliest factories in England came up by the 1730s. But it was only in the late eighteenth century that the number of factories multiplied.

- In 1970 Britain was importing 2.5 million pounds of raw cotton to feed its cotton industry. By 1787 this import soared to 22 million pounds.

- A series of inventions in the eighteenth century increased the efficiency of each step of the production process (carding, twisting and spinning, and rolling).

- Then Richard Arkwright created the cotton mill. Till this time, as you have seen, cloth production was spread all over the countryside and carried out within village households.

- Now costly new machines could be purchased, set up and maintained in the mills. Within the mills all the process were brought together under one roof and management.

- This allowed a more careful supervision over the production process, a watch over quality, and the regulation of labour, all of which had been difficult to do when production was in the countryside.

- In the early nineteenth century, factories increasingly become an intimate part of the English landscape.

THE PACE OF INDUSTRIAL CHANGE:

(i) Main industries: Cotton and metal industries were the most dynamic industries in Britain. Cotton was the leading sector in the first phase of industrialisation up to the 1840s but the iron and steel industry led the way after 1840. By 1873 Britain was exporting iron and steel worth about $77 million, double the value of its cotton export.

(ii) Domination of traditional industry: The modern machinery and, industries could not easily displace traditional industries. Even at the end of the nineteenth century, less than 20 percent of the total work force was employed in technologically advanced industrial sectors.

(iii) Base for growth: The pace of change in the `traditional' industries was not set by steam powered cotton or metal industries. It was the ordinary and small innovation which built up the basis of growth in many non-mechanised sectors.

(iv) Slow pace: Though technological inventions were taking place but their pace was very slow. They did not spread dramatically across the industrial landscape. New technologies and machines were expensive so the producers and the industrialists were cautious about using them. The machines often broke down and repair was Costly. They were not as effective as their inventors and manufacturers claimed.

COEXISTENCE OF HAND LABOUR AND STEAM POWER:

In Victorian Britain there was no shortage of human labour. Poor peasants and vagrants moved to the cities in large numbers in search of jobs, waiting for work.

So industrialists had no problem of labour shortage or high wage costs. They did not want to introduce machines that got rid of human labour and required large capital investment.

In many industries the demand for labour was seasonal. Gas works and breweries were especially busy through the cold months. So they needed more workers to meet their peak demand. Bookbinders and printers, catering to Christmas demand, too needed extra hands before December. At the waterfront, winter was the time that ships were repaired and spruced up. In all such industries where production fluctuated with the season, industrialists usually preferred hand labour, employing workers for the season.

POPULARITY OF INTRICATE DESIGNS:

A range of products could be produced only with hand labour. Machines were oriented to producing uniforms, standardised goods for a mass market. But the demand in the market was often for goods with intricate designs and specific shapes. In mid-nineteenth-century Britain, for instance, 500 varieties of hammers were produced and 45 kinds of axes. These required human skill, not mechanical technology.

In Victorian Britain, the upper classes – the aristocrats and the bourgeoisie – preferred things produced by hand. Handmade products came to symbolise refinement and class. They were better finished, individually produced, and carefully designed. Machinemade goods were for export to the colonies.

In countries with labour shortage, industrialists were keen on using mechanical power so that the need for human labour can be minimised. This was the case in nineteenth-century America. Britain, however, had no problem hiring human hands.

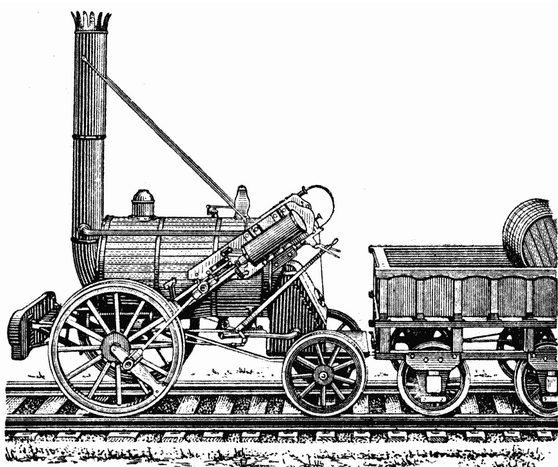

Steam Engine

LIFE OF THE WORKERS:

The process of industrialisation brought with it miseries for newly emerged class of industrial workers.

(i) Abundance of labour: As news of possible jobs travelled to the countryside, hundreds tramped to the cities. But everyone was not lucky enough to get an instant job. Many job-seekers had to wait weeks, spending nights under bridges or in night shelters. Some stayed in Night Refuge that was set up by private individuals; other went to the Casual Wards maintained by the Poor Law authorities.

(ii) Seasonality of work: Seasonality of work in many industries meant prolonged periods without work. After the busy season was over, the poor were on the streets again. They either returned to the countryside or looked for odd jobs, which till the mid-nineteenth century were difficult to find.

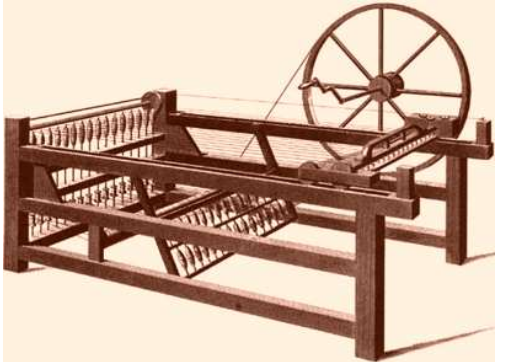

(iii) Poverty and unemployment: At the best of times till the mid-nineteenth century, about 10% of the urban population was extremely poor which went up to anything between 35 and 75% during periods of economic slump. The fear of unemployment made workers hostile to the introduction of new technology. When the Spinning Jenny was introduced in the woollen industry, women who survived On hand spinning began attacking the new machines. After the 1840s, building activity intensified in the cities, opening up greater opportunities of employment.

A Spinning Jenny by T.E. Nicholson