Post – War Recovery

The Making Of Global World of Class 10

Post – War Recovery

➢ Post-war economic recovery proved difficult. Britain, which was the world’s leading economy in the pre-war period, in particular faced a prolonged crisis. While Britain was preoccupied with war, industries had developed in India and Japan.

➢ After the war Britain found it difficult to recapture the Indian market.

➢ To finance war expenditures Britain had borrowed liberally from the US. This meant that at the end of the war Britain was burdened with huge external debts.

➢ The war had led to an economic boom, that is, to a large increase in demand, production and employment. When the war boom ended, production contracted and unemployment increased.

➢ At the same time the government reduced bloated war expenditures to bring them into line with peacetime revenues.

➢ This led to huge job losses. Anxiety and uncertainty about work became an enduring part of post-war scenario.

➢ The war also disrupted agricultural economies of Asia and Africa facing a crisis. Consider the case of wheat producers.

➢ Before the war, Eastern Europe was a major supplier of wheat in the world market. When this supply was disrupted during the war, wheat production in Canada, America and Australia expanded dramatically.

➢ But once the war was over, production in Eastern Europe revived and created a glut in wheat output. Grain prices fell, rural incomes declined, and farmers fell deeper into debt.

RISE OF MASS PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION:

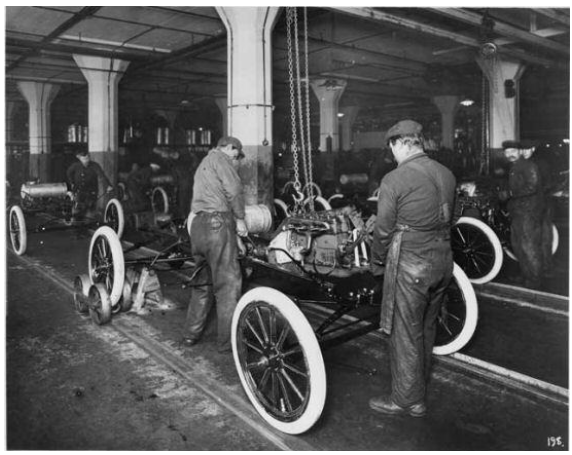

One important feature of the US economy of the 1920s was mass production. The move towards mass production had begun in the late nineteenth century, but in the 1920s it became a characteristic feature of industrial production in the US. A well-known pioneer of mass production was the car manufacturer Henry Ford. He adapted the assembly line of a Chicago slaughterhouse (in which slaughtered animals were picked apart by butchers as they came down a conveyor belt) to his new car plant in Detroit. He realised that the ‘assembly line’ method would allow a faster and cheaper way of producing vehicles. The assembly line forced workers to repeat a single task mechanically and continuously – such as fitting a particular part to the car – at a pace dictated by the conveyor belt. This was a way of increasing the output per worker by speeding up the pace of work. Standing in front of a conveyor belt no worker could afford to delay the motions, take a break, or even have a friendly word with a workmate. As a result, Henry Ford’s cars came off the assembly line at three-minute intervals, a speed much faster than that achieved by previous methods. The T Model Ford was the world’s first mass-produced car.

Mass Production of T-automobiles

Even today Business Schools teach reams of pages on Fordism, the management philosophy of Henry Ford.

Mass production lowered costs and prices of engineered goods. Thanks to higher wages, more workers could now afford to purchase durable consumer goods such as cars. Car production in the US rose from 2 million in 1919 to more than 5 million in 1929. Similarly, there was a spurt in the purchase of refrigerators, washing machines, radios, gramophone players, all through a system of ‘hire purchase’ (i.e., on credit repaid in weekly or monthly instalments). The demand for refrigerators, washing machines, etc. was also fuelled by a boom in house construction and home ownership, financed once again by loans.

The housing and consumer boom of the 1920s created the basis of prosperity in the US. Large investments in housing and household goods seemed to create a cycle of higher employment and incomes, rising consumption demand, more investment, and yet more employment and incomes.

In 1923, the US resumed exporting capital to the rest of the world and became the largest overseas lender. US imports and capital exports also boosted European recovery and world trade and income growth over the next six years.

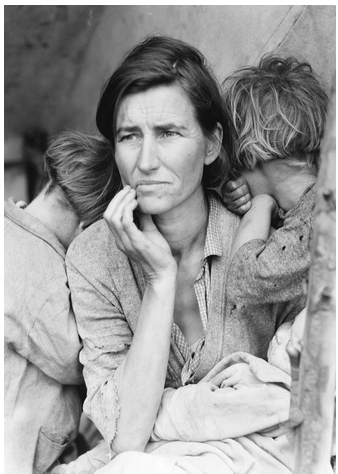

THE GREAT DEPRESSION

➢ The Great Depression began around 1929 and lasted till the mid 1930s. During this period most parts of the world experienced catastrophic declines in production, employment, incomes and trade. The exact timing and impact of the depression varied across countries. But in general agricultural regions and communities were the worst affected.

Great Economic Depression

➢ This was because the fall in agricultural prices was greater and more prolonged than that in the prices of industrial goods.

➢ The depression was caused by a combination of several factors. We have already seen how fragile the post-war world economy was.

➢ First: agricultural overproduction remained a problem. This was made worse by falling agricultural prices. As prices slumped and agricultural incomes declined, farmers tried to expand production and bring a larger volume of produce to the market to maintain their overall income. This further lowered the prices.

➢ Second in the mid- 1920s may countries financed their investments through loans from the US. While it was often extremely easy to raise loans in the US when the going was goods, US overseas lenders panicked at the first sign of trouble.

➢ The withdrawal of US loans affected much of the rest of the world, though in different ways. In Europe it led to the failure of some major banks and the collapse of currencies such as the British pound sterling. In Latin America and elsewhere it intensified the slump in agricultural and raw material prices.

➢ Overproduction also led to the closure of factories. Unemployment soared high.

➢ The US was also the industrial country most severely affected by the depression. With the fall in prices and the prospect of a depression, US banks had also slashed domestic lending and called back loans.

➢ Faced with falling incomes, many households in the US could not repay what they had borrowed, and were forced to give up their homes, cars and other consumer durables.

➢ As unemployment soared, people moved long distances looking for any work they could find. Ultimately, the US banking system itself collapsed. Unable to recover investments, collect loans and repay depositors.

➢ Ultimately, the US banking system itself collapsed. Unable to recover investments, collect loans and repay depositors, thousands of banks went bankrupt and were forced to close.

➢ The numbers are phenomenal: by 1933 over 4,000 banks had closed and between 1929 and 1932 about 110,000 companies had collapsed.

➢ By 1935, a modest economic recovery was under way in most industrial countries.