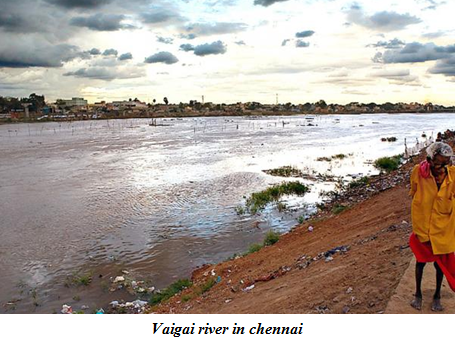

Water Supply to Chennai

Water and the People of Chennai of Class 8

Is It Available To All?

While there is no doubt that public facilities should be made available to all, in reality, there is a great shortage of such facilities. The water supply in Chennai is marked by shortages. Municipal supply meets only about half the needs of the people of the city, on average.

There are areas that get water more regularly than others. Those areas that are close to the storage points get more water whereas colonies further away receive less water. The burden of shortfalls in water supply fails mostly on the poor.

The middle class, when faced with water shortages, is able to cope through a variety of private means such as digging borewells, buying water from tankers, and using bottled water for drinking. Apart from the availability of water, access to `safe' drinking water is also available to some and this depends on what one can afford.

People who can afford it have safe drinking water, whereas the poor are again left out. In reality, therefore, it seems that it is only people with money who have the right to water - a far cry from the goal of universal access to sufficient and safe' water.

In Search of Alternative

The shortage in municipal water is increasingly being filled by an expansion of private companies who are selling water for profit. The supply of water per person in an urban area in India should be about 135 liters per day (about seven buckets) - a standard set by the Urban Water Commission.

Whereas people in slums have to make do with less than 20 liters a day per person (one bucket), people living in luxury hotels may consume as much as 1,600 liters (80 buckets) of water per day. A shortage of municipal water is often taken as a sign of failure by the government.

Why water supply should not be given to private companies ?

- Throughout the world, water supply is a function of the government. There are very few instances of private water supply.

- There are areas in the world where the public water supply has achieved universal access.

- When the responsibility for water supply was handed over to private companies, there was a steep rise in the price of water, making it unaffordable for many. Cities saw huge protests, with riots breaking out in places like Bolivia, forcing the government to take back the service from private hands.

- Within India, there are cases of success in government water departments, though these are few in number and limited to certain areas of their work.

Conclusion

- Public facilities relate to our basic needs and the Indian Constitution recognizes the right to water, health, education, etc. as being a part of the Right to Life. Thus one of the major roles of the government is to ensure adequate public facilities for everyone.

- But, progress on this front has been far from satisfactory. Handing over these facilities to private companies may not be the answer. Any solution needs to take account of the important fact that every citizen of the country has a right to these facilities which should be provided to her/him in an equitable manner.