Static equilibrium is stationary, with no observable changes. Dynamic equilibrium involves microscopic changes, such as forward and reverse reactions in chemical reactions. Reversible reactions can occur in both directions.

For example: A +B ⇌ C + D

At the beginning of a reaction, the rate of the forward reaction is typically faster. As reactants are used up and products form, the reverse reaction speeds up. Over time, the two rates become equal, and the system reaches a dynamic equilibrium. At equilibrium, the concentration of reactants and products remains constant over time, but they aren't necessarily equal.Law of Chemical Equilibrium

For a general reversible reaction:aA + bB ⇌ cC+ dD

The rate of the forward reaction is directly proportional to the concentrations of the reactants raised to the power of stoichiometric coefficients:Rate forward ∝ [A] a [B] b

Similarly, the rate of the reverse reaction is proportional to the concentrations of the products:Rate reverse ∝ [C] c [D] d

At equilibrium, these two rates are equal: Rate forward = Rate reverseEquilibrium Constant (K)

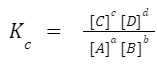

For the general reaction:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD , the equilibrium constant, Kc, is given by:

where the brackets denote the concentration of the species at equilibrium. The value of K c can provide insights about the extent of a reaction. A large K c means the reaction largely produces products, while a small Kc means mostly reactants are present at equilibrium.

The concentrations are usually given in molarity (M). The letters a, b, c, and d represent the stoichiometric coefficients in the balanced chemical equation. [A], [B], [C], and [D] indicate the equilibrium concentrations of the species.

where the brackets denote the concentration of the species at equilibrium. The value of K c can provide insights about the extent of a reaction. A large K c means the reaction largely produces products, while a small Kc means mostly reactants are present at equilibrium.

The concentrations are usually given in molarity (M). The letters a, b, c, and d represent the stoichiometric coefficients in the balanced chemical equation. [A], [B], [C], and [D] indicate the equilibrium concentrations of the species.

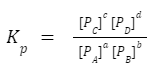

Equilibrium constant in terms of partial pressure:

If the reaction involves gases, the equilibrium constant can also be expressed in terms of partial pressures, denoted as Kp. The relation between K p and K c is:

The relation between K p and K c is:

Kp = Kc (RT) Δn

Where R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature in Kelvin, and Δn is the change in moles of gaseous reactants and products.Download PDF Equilibrium Formula

Reaction Quotient (Q)

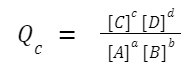

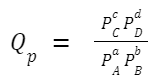

The reaction quotient, Q, is calculated in the same way as the equilibrium constant, K, but the concentrations or partial pressures used in the formula are those that exist at any given moment in time, not just at equilibrium. For a generic chemical reaction: aA +bB ⇌ cC + dD The reaction quotient, Q c (in terms of concentration), is given by: If you're working with gaseous reactions and using partial pressures, you'd denote the reaction quotient as Q

p

. The formula is analogous, but with partial pressures instead of concentrations:

If you're working with gaseous reactions and using partial pressures, you'd denote the reaction quotient as Q

p

. The formula is analogous, but with partial pressures instead of concentrations:

Where: [A], [B], [C], and [D] are the concentrations (or partial pressures for Q

p

) of the reactants and products at a specific time. a, b, c, and d are the stoichiometric coefficients.

Where: [A], [B], [C], and [D] are the concentrations (or partial pressures for Q

p

) of the reactants and products at a specific time. a, b, c, and d are the stoichiometric coefficients.

Importance of the Reaction Quotient:

Comparison with Equilibrium Constant (K): If Q=K : The system is at equilibrium. If Q>K: There is too much product or too little reactant. The reaction shifts to the left (toward the reactants) to attain equilibrium. If Q<K: There is too much reactant or too little product. The reaction will shift to the right (toward the products) to reach equilibrium.Also Check: List of Chemistry Formulas

Le Chatelier's Principle

States that if a system at equilibrium is disturbed by a change in temperature, pressure, or the concentration of one of the components, the system will shift its position to counteract that disturbance. For instance, if you increase the concentration of a reactant, the system might shift to produce more products.Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG)

Gibb's free energy relates to the spontaneity of a process. For a process at constant temperature and pressure ΔG=ΔG ∘ +RT ln(Q) Where: ΔG = change in Gibbs free energy for the reaction. ΔG ∘ = standard Gibbs free energy change (when Q=1). R = universal gas constant (8.314 J/(mol·K)). T = temperature in Kelvin. Q = reaction quotient.Relation between ΔG ∘ and K:

ΔG ∘ =−RT ln(K)

Observations: If ΔG<0: The reaction is spontaneous in the forward direction. If ΔG>0: The reaction is non-spontaneous in the forward direction, but spontaneous in the reverse direction. If ΔG=0: The system is at equilibrium and Q=K.Ionic Product of Water (Kw)

Pure water is slightly ionized and at equilibrium, the concentration of H + ions equals the concentration of OH − ions.H 2 O ⇌ H + + OH –

K w = [H + ] [OH − ]

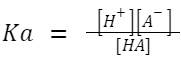

At 25°C, K w is 1.0×10 −14 mol 2 /L 2Ionization Constant of Weak Acid (Ka): A weak acid doesn't fully ionize in a solution. If HA is a weak acid,

then: HA ⇌ H + +A – A larger K a value indicates a stronger weak acid.

A larger K a value indicates a stronger weak acid.

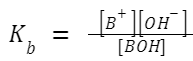

Ionization Constant of Weak Base (K b ): Similarly, a weak base doesn't fully ionize in a solution. If BOH is a weak base,

then: BOH ⇌ B + + OH – A larger K

b

value indicates a stronger weak base.

A larger K

b

value indicates a stronger weak base.

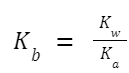

Relationship between K a and K b : For a weak acid and its conjugate base or a weak base and its conjugate acid:

K w =K a × K b

So, if you know K a for a weak acid, you can determine K b for its conjugate base using the formula: Similarly, if you know K

b

for a weak base, you can determine K

a

for its conjugate acid.

Similarly, if you know K

b

for a weak base, you can determine K

a

for its conjugate acid.

Also read: Aluminum Acetate Formula

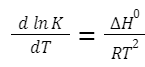

Thermodynamics of Equilibrium

In the context of chemical equilibrium, thermodynamics helps relate the position of equilibrium to thermodynamic properties like enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy. The equilibrium constant, K, is directly related to the Gibbs free energy change, ΔG, for the reaction. Gibbs Free Energy:ΔG=ΔH−TΔS

ΔG = Gibbs free energy change ΔH = Enthalpy change T = Absolute temperature (in Kelvin) ΔS = Entropy change Relation to Equilibrium Constant:Van't Hoff Equation

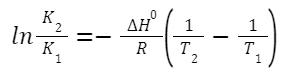

The Van't Hoff equation relates the temperature dependence of the equilibrium constant to the enthalpy change of the reaction. Integrated Form (over a temperature range):

Integrated Form (over a temperature range):

K

1

and K

2

indicate equilibrium constants at temperatures T

1

and T

2

, respectively.

K

1

and K

2

indicate equilibrium constants at temperatures T

1

and T

2

, respectively.

Also Check: Acids and Bases Formula

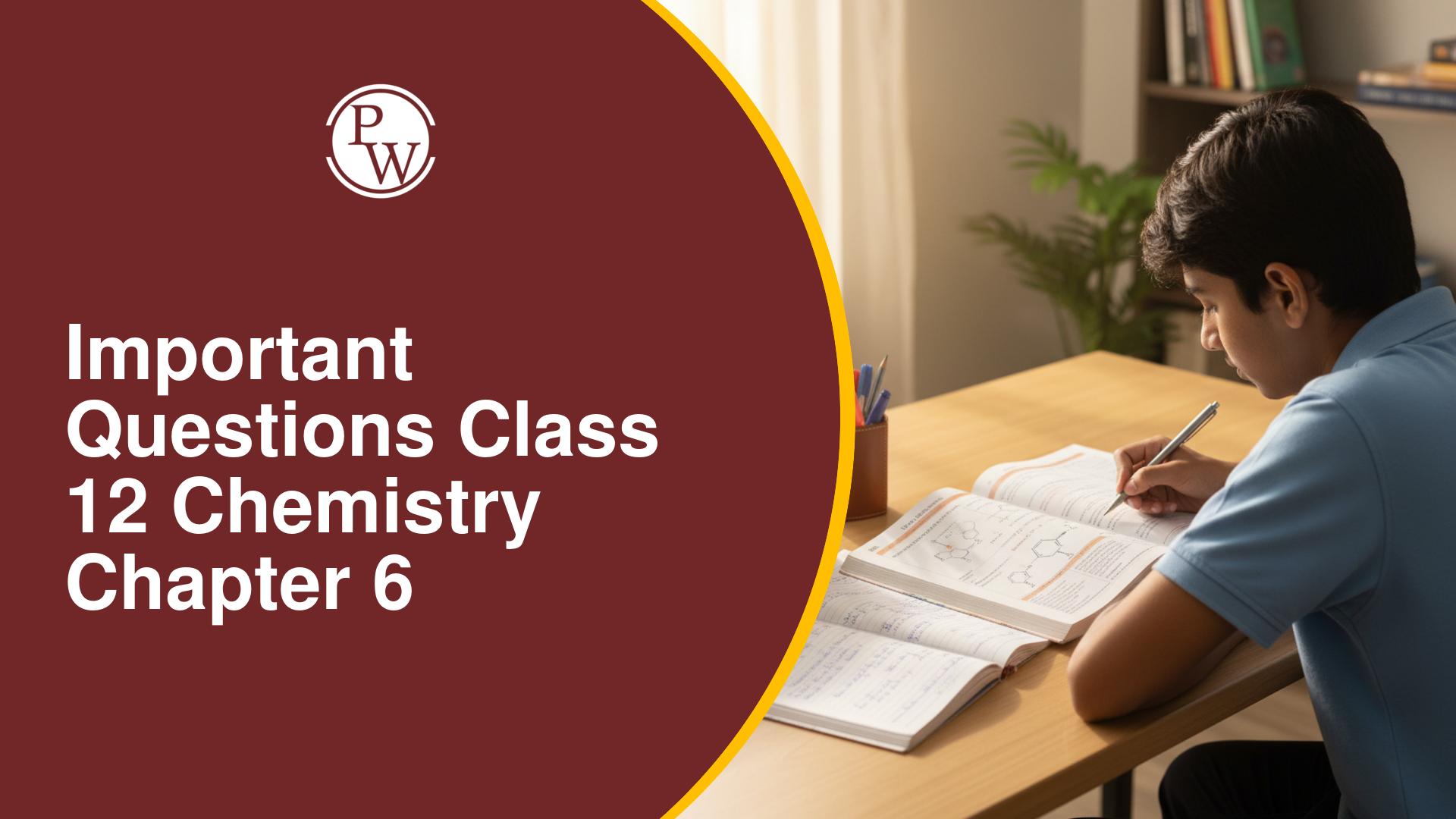

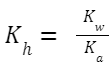

Salt Hydrolysis

Salts undergo hydrolysis when dissolved in water, producing acidic or basic solutions. Strong acids and bases don't undergo hydrolysis, while weak acids and bases produce basic or acidic solutions.Salt of a Weak Acid and Strong Base (e.g., CH 3 COONa):

CH 3 COO − + H 2 O ⇌ CH 3 COOH + OH –

Hydrolysis Constant, K h (also sometimes denoted by K w /K a ): Where K

w

is the ionic product of water, and K

a

is the ionization constant of the weak acid (in this case, CH

3

COOH).

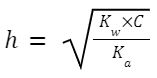

Degree of hydrolysis,

Where K

w

is the ionic product of water, and K

a

is the ionization constant of the weak acid (in this case, CH

3

COOH).

Degree of hydrolysis,

C is the concentration of the salt.

C is the concentration of the salt.

Concentration of OH

[OH − ]=h × C

pOH: = − log [OH] -

pH=14−pOH

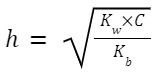

Salt of a Strong Acid and Weak Base (e.g., NH 4 Cl):

NH 4 + +H 2 O ⇌ NH 3 +H 3 O +

Hydrolysis Constant, K h (also sometimes denoted by K w /K b ):

[H 3 O + ] = ℎ × C

pH = −log [H + ]

Equilibrium Formula FAQs

Q1. What does a large K c value indicate?

Q2. What's Le Chatelier's Principle?

Q3. What's the difference between strong and weak electrolytes?

Q4. What is ionic equilibrium?

Q5. What is pKa?