Migration For Employment Opportunities

The Age Of Industrialization of Class 10

Migration For Employment Opportunities

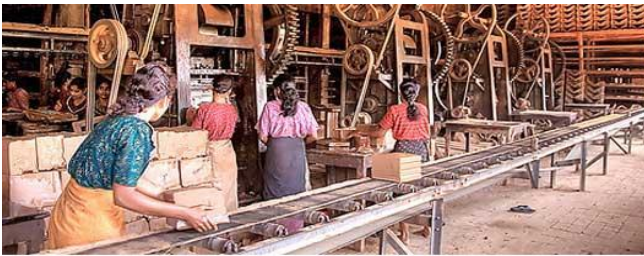

Factories needed workers. With the expansion of factories, this demand increased. In 1901, there were 584,000 workers in Indian factories. By 1946 the number was over 2,436, 000.

In most industrial regions workers came from the districts around. Peasants and artisans who found no work in the village went to the industrial centres in search of work. Over 50 per cent workers in the Bombay cotton industries in 1911 came from the neighbouring district of Ratnagiri, while the mills of Kanpur got most of their textile hands from the villages within the district of Kanpur. Most often millworkers moved between the village and the city, returning to their village homes during harvests and festivals.

Over time, as news of employment spread, workers travelled great distances in the hope of work in the mills. From the United Provinces (Modern UP or Uttar Pradesh), for instance, they went to work in the textile mills of Bombay and in the jute mills of Calcutta.

Getting jobs was always difficult, even when mills multiplied and the demand for workers increased. The numbers seeking work were always more than the jobs available. Entry into the mills was also restricted. Industrialists usually employed a jobber to get new recruits. Very often the jobber was an old and trusted worker. He got people from his village, ensured them jobs, helped them settle in the city and provided them money in times of crisis. The jobber therefore became a person with some authority and power. He began demanding money and gifts for his favour and controlling the lives of workers.

THE PECULIARITIES OF INDUSTRIAL GROWTH:

(i) European Managing Agencies, which dominated industrial production in India, were interested in certain kinds of products. They established tea and coffee plantations, acquiring land at cheap rates from the colonial government; and they invested in mining, indigo and jute.

(ii) When Indian businessmen began setting up industries in the late nineteenth century, they avoided competing with Manchester goods in the Indian market.

(iii) By the first decade of the twentieth century a series of changes affected the pattern of industrialisation. Industrial groups organised themselves to protect their collective interests, pressurising the government to increase tariff protection and grant other concessions.

(iv) Till the First World War, industrial growth was slow. The war created a dramatically new situation. With British mill busy with war production to meet the needs of the army, Manchester imports into India declined. Suddenly, Indian mills had a vast home market to supply. As the war prolonged, Indian factories were called upon to supplywar needs. New factories were set up and old ones ran multiple shifts. Many new workers were employed and everyone was made to work longer hours. Over the war years industrial production boomed.

(v) After the war, within the colonies, local industrialists gradually consolidated their position, substitute foreign manufactures and capturing the home market.

DOMINANCE OF SMALL-SCALE INDUSTRIES:

While factory industries grew steadily after the war, large industries formed only a small segment of the economy. Most of them – about 67 per cent in 1911 – were located in Bengal and Bombay.

Over the rest of the country, small-scale production continued to predominate. Only a small proportion of the total industrial labour force worked in registered factories: 5 per cent in 1911 and 10 per cent in 1931. The rest worked in small workshops and household units, often located in alleys and bylanes, invisible to the passer-by. In fact, in some instances, handicrafts production actually expanded in the twentieth century. This is true even in the case of the handloom sector that we have discussed. While cheap machine-made thread wiped out the spinning industry in the nineteenth century, the weavers survived, despite problems. In the twentieth century, handloom cloth production expanded steadily: almost trebling between 1900 and 1940.

This was partly because of technological changes. Handicrafts people adopt new technology if that helps them improve production without excessively pushing up costs. So, by the second decade of the twentieth century we find weavers using looms with a fly shuttle. This increased productivity per worker, speeded up production and reduced labour demand. By 1941, over 35 percent of handlooms in India were fitted with fly shuttles: in regions like Travancore, Madras, Mysore, Cochin, Bengal the proportion was 70 to 80 per cent. There were several other small innovations that helped weavers improve their productivity and compete with the mill sector.

Certain groups of weavers were in a better position than others to survive the competition with mill industries. Amongst weavers some produced coarse cloth while others wove finer varieties. The coarser cloth was bought by the poor and its demand fluctuated violently. In times of bad harvests and famines, when the rural poor had little to eat, and their cash income disappeared, they could not possibly buy cloth. The demand for the finer varieties bought by the well-to-do was more stable. The rich could buy these even when the poor starved. Famines did not affect the sale of Banarasi or Baluchari sarees. Moreover, as you have seen, mills could not imitate specialised weaves. Saris with woven borders, or the famous lungis and handkerchiefs of Madras, could not be easily displaced by mill production.

Weavers and other craftspeople who continued to expand production through the twentieth century, did not necessarily prosper. They lived hard lives and worked long hours. Very often the entire household – including all the women and children – had to work at various stages of the production process. But they were not simply remnants of past times in the age of factories. Their life and labour was integral to the process of industrialisation.

MARKET FOR GOODS:

(i) British manufacturers attempted to take over the Indian market on the other hand Indian weavers and craftsmen, traders and industrialists resisted colonial controls, demanded tariff protection, created their own spaces, and tried to extend the market for their produce.

(a) Methods Used by Producers to Expand their Markets:

(i) Advertisement: Advertisements make products appear desirable and necessary. They try to shape the minds of people and create new needs. From the very beginning of the industrial age, advertisements have played a part in expanding the markets for products, and in shaping a new consumer culture.

(ii) Labeling: When Manchester industrialists began selling cloth in India, they put labels on the cloth bundles. The label was needed to make the place of manufacture and the name of the company familiar to the buyer. The label was also to be a mark of quality. When buyers saw ‘MADE IN MANCHESTER’ written in bold on the label, they were expected to feel confident about buying the cloth. Labels also carried images and were very often beautifully illustrated.

(iii) Calendars: By the nineteenth century, manufacturers were printing calendars to popularise their products. Unlike newspapers and magazines, calendars were used even by people who could not read. They were hung in tea shops and in poor people's homes just as much as in offices and middle class apartments. And those who hung the calendars had to see the advertisements, day after day, through the year. Even in these calendars images of gods and goddesses were used to attract the consumers.

(iv) Images of gods, goddesses and personages: Images of Indian gods and goddesses regularly appeared on labels. It was as if the association with gods gave divine approval to the goods being sold, was also intended to make the manufacture from a foreign land appear somewhat familiar to Indian people. Like the images of gods, figures of important personages, of emperors and nawabs, adorned advertisements and calendars. The message: if your respect the royal figure, then respect this product; when the product was being used by kings, or produced under royal command, its quality could not be questioned.

(v) Advertisement by Indian producers: When Indian manufacturers advertised the nationalist message was clear and loud. If you care for the nation then buy products that Indians produce. Advertisements became a vehicle of the nationalist message of Swadeshi.