The City In Colonial India

Work, Life And Leisure of Class 10

The City In Colonial India

Indian cities did not mushroom in the nineteenth century. The pace of urbanisation in India was slow under colonial rule. A large proportion of these urban dwellers were residents of the three Presidency cities. These were multi-functional cities: they had major ports, warehouses, homes and offices, army camps, as well as educational institutions, museums and libraries. Bombay was the premier city of India.

BOMBAY:

In the seventeenth century, Bombay was a group of seven islands under Portuguese control. In 1661, control of the islands passed into British hands after the marriage of Britain’s King Charles II to the Portuguese princess. The East India Company quickly shifted its base from Surat, its principal western port, to Bombay. At first, Bombay was the major outlet for cotton textiles from Gujarat. Later, in the nineteenth century, the city functioned as a port through which large quantities of raw materials such as cotton and opium would pass. Gradually, it also became an important administrative centre in western India, and then, by the end of the nineteenth century, a major industrial centre.

WORK IN THE CITY:

Bombay became the capital of the Bombay Presidency in 1819, after the Maratha defeat in the Anglo-Maratha war. The city quickly expanded. With the growth of trade in cotton and opium, large communities of traders and bankers as well as artisans and shopkeepers came to settle in Bombay. The establishment of textile mills led to a fresh surge in migration.

The first cotton textile mill in Bombay was established in 1854. By 1921, there were 85 cotton mills with about 146,000 workers. Only about one-fourth of Bombay’s inhabitants between 1881 and 1931 were born in Bombay: the rest came from outside. Large numbers flowed in from the nearby district of Ratnagiri to work in the Bombay mills. Women formed as much as 23 per cent of the mill workforce in the period between 1919 and 1926. After that, their numbers dropped steadily to less than 10 percent of the total workforce. By the late 1930s, women’s jobs were increasingly taken over by machines or by men.

Bombay dominated the maritime trade of India till well into the twentieth century. It was also at the junction head of two major railways. The railways encouraged an even higher scale of migration into the city. For instance, famine in the dry regions of Kutch drove large numbers of people into Bombay in 1888-89. The flood of migrants in some years created panic and alarm in official circles.

Worried by the influx of population during the plague epidemic of 1898, district authorities sent about 30,000 people back to their places of origin by 1901.

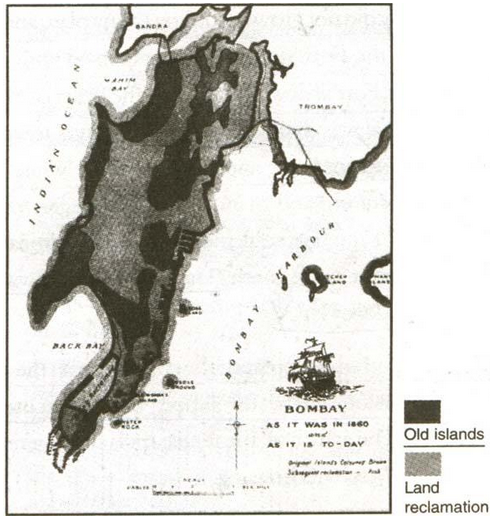

A map of Bombay in the 1930s showing the seven islands and the reclamations

Housing and Neighborhoods:

(i) Bombay was a crowded city. From it earliest days, Bombay did not grow according to any plan, and houses especially in the Fort area, were interspersed with gardens.

(ii) With the rapid and unplanned expansion of the city, the crisis of housing and water supply became acute by the mid-1850s.

(iii) The richer Parsi, Muslim and upper-caste traders and industrialists of Bombay lived in sprawling, spacious bungalows. More than 70 percent of the working people lived in the thickly chawls of Bombay

(iv) Chawls were multistoried structures largely owned by private landlords, looking for quick ways of earning money from anxious migrants. Each chawl was divided into smaller one-room tenements which had no private toilets.

(v) Many families could reside at a time in a tenement. High rents forced workers to share homes, either with relatives or caste fellows who were streaming into the city. Though water was scarce, and people often quarreled every morning for a turn at the tap, observers found that houses were kept quite clean.

(vi) The homes being small, streets and neighborhoods were used for a variety of activities such as cooking, washing and sleeping. Streets were also used for different types of leisure activities.

(vii)Caste and family groups in the mill neighbourhoods were headed by someone who was similar to a village headman. He settled disputes, organised food supplies, or arranged informal credit. He also brought important information on political developments.

(viii) People who belonged to the `depressed classes' were kept out of many chawls and often had to live in shelters made of corrugated sheets, leaves, or bamboos poles.

(ix) Planning in Bombay came about as a result of fears about the plague epidemic. The City of Bombay Improvement Trust was established in 1898; it focused on clearing poorer homes out of the city centre. In 1918, a Rent Act was passed to keep rents reasonable.

LAND RECLAMATION IN BOMBAY:

The seven islands of Bombay were joined into one landmass only over a period of time. The earliest project began in 1784. The Bombay governor William Hornby approved the building of the great sea wall which prevented the flooding of the low-lying areas of Bombay. Since then, there have been several reclamation projects.

The need for additional commercial space in the mid-nineteenth century led to the formulation of several plans, both by government and private companies, for the reclamation of more land from the sea. Private companies became more interested in taking financial risks. In 1864, the Back Bay Reclamation Company won the right to reclaim the western foreshore from the tip of Malabar Hill to the end of Colaba. Reclamation often meant the levelling of the hills around Bombay. By the 1870s, although most of the private companies closed down due to the mounting cost, the city had expanded to about 22 square miles.

As the population continued to increase rapidly in the early twentieth century, every bit of the available area was built over and new areas were reclaimed from the sea. A successful reclamation project was undertaken by the Bombay Port Trust, which built a dry dock between 1914 and 1918 and used the excavated earth to create the 22-acre Ballard Estate. Subsequently, the famous Marine Drive of Bombay was developed.

A familiar landmark of Bombay, it was built on land reclaimed from the sea in the twentieth century.

BOMBAY AS THE CITY OF DREAMS:

THE WORLD OF CINEMA AND CULTURE

- Despite its massive overcrowding and difficult living conditions, Bombay appears to many as a ‘mayapuri’ a city of dreams.

- Many Bombay films deals with the arrival in the city of new migrants, and their encounters with the real pressures of daily life.

- Some popular songs from the Bombay film industry speak of the contradictory aspects of the city.

- In the film CID (1956) the hero’s buddy sings, ‘Ai dil hai mushkil jeena yahan, zara hatke zara bachke, ye hai Bambai meri jaan’ (my heart, it is difficult to live here, move over a little, take care of yourself! this is Bombay my love.

- Harishchandra Sakharam Bhatwadekar shot a scene of a wrestling match in Bombay’s Hanging Gardens and it became India’s first movie in 1896.

- Soon after, Dadasaheb Phalke made Raja Harishchandra (1913). After that, there was no turning back. By 1925, Bombay had become India’s film capital, producing films for a national audience.

- Most of the people in the film industry were themselves migrants who came from cities like Lahore, Calcutta, Madras and contributed to the national character of the industry. Those who came from Lahore, then in Punjab, were especially important for the development of the Hindi film industry.

- Many famous writers, like Ismat Chughtai and Saadat Hasan Manto, were associated with Hindi cinema.

- Bombay films have contributed in a big way to produce an image of the city as a blend of dream and reality, or slums and star bungalows.

For wealthy Britishers, there had long been an annual ‘London Season’. Several cultural events, such as the opera, the theatre and classical music performances were organised for an elite group of 300-400 families in the late eighteenth century. Meanwhile, working classes met in pubs to have a drink, exchange news and sometimes also to organise for political action. Many new types of large-scale entertainment for the common people came into being, some made possible with money from the state. Libraries, art galleries and museums were established in the nineteenth century to provide people with a sense of history and pride in the achievements of the British. At first, visitors to the British Museum in London numbered just about 15,000 every year, but when entry was made free in 1810, visitors swamped the museum: their number jumped to 127,643 in 1824-25, shooting up to 825, 901 by 1846. Music halls were popular among the lower classes, and, by the early twentieth century, cinema became the great mass entertainment for mixed audiences.

Pleasure gardens came in the nineteenth century to provide facilities for sports, entertainment and refreshments for the well-to-do.

- Libraries, art galleries and museums were established in the nineteenth century to provide people with a sense of history and pride in the achievements of the British.

- Music halls were popular among lower classes. By the early twentieth century cinema became the great mass entertainment for mixed audience.

- British industrial workers were increasingly encouraged to spend their holiday by the sea, so as to derive the benefits of the sun and bracing winds.

The working poor created spaces of entertainment wherever they lived.

POLITICS IN THE CITY:

In the severe winter of 1886, when outdoor work came to a standstill, the London poor exploded in a riot, demanding relief from the terrible conditions of poverty. Alarmed shopkeepers closed down their establishments, fearing the 10,000-strong crowd that was marching from Deptford to London. The marchers had to be dispersed by the police. A similar riot occurred in late 1887; this time, it was brutally suppressed by the police in what came to be known as the Bloody Sunday of November 1887. Two years later, thousands of London’s dock workers went on strike and marched through the city.

These are good example of how large masses of people could be drawn into political causes in the city. A large city population was thus both a threat and an opportunity. State authorities went to great lengths to reduce the possibility of rebellion and enhance urban aesthetics. Better town planning was carried out with lots of greenery and open spaces to induce a sense of calm. This was believed to help produce more responsible citizens.